As a home for nonprofits, foundations, and corporate allies engaged in every kind of charitable endeavor, Independent Sector is proud to advance the work of volunteers across the country. In the interest of further advancing the national dialogue on volunteerism and national service, we are proud to introduce this blog series, Reimagining Volunteerism & Service, to dig deeper and explore different policy solutions in 2020 and beyond. Today, Kaitlin Ahmad, Nathan Dietz , and Robert T. Grimm, Jr., of the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute explore how volunteering trends have changed during the 21st century. We encourage you to share your reactions and thoughts to this blog post in the comments below.

While the future of philanthropy is a hot topic today, few recognize that both volunteering and giving rates began a long decline early in the 21st century. Even fewer discuss how informal behaviors such as talking to your neighbors and doing favors for them are also fading. (More on that in our upcoming publication, Maryland Civic Health Report). Given that volunteering, donating, and neighborhood engagement often go “hand in hand,” we find ourselves living in a world where fewer people act philanthropically in all kinds of ways. To change that dynamic and regain our strong ties of community, we need to better understand these trends. In this blog, we use data collected (2002-2015) by the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to highlight America’s changing volunteer landscape.*

Volunteers Down, Hours Up

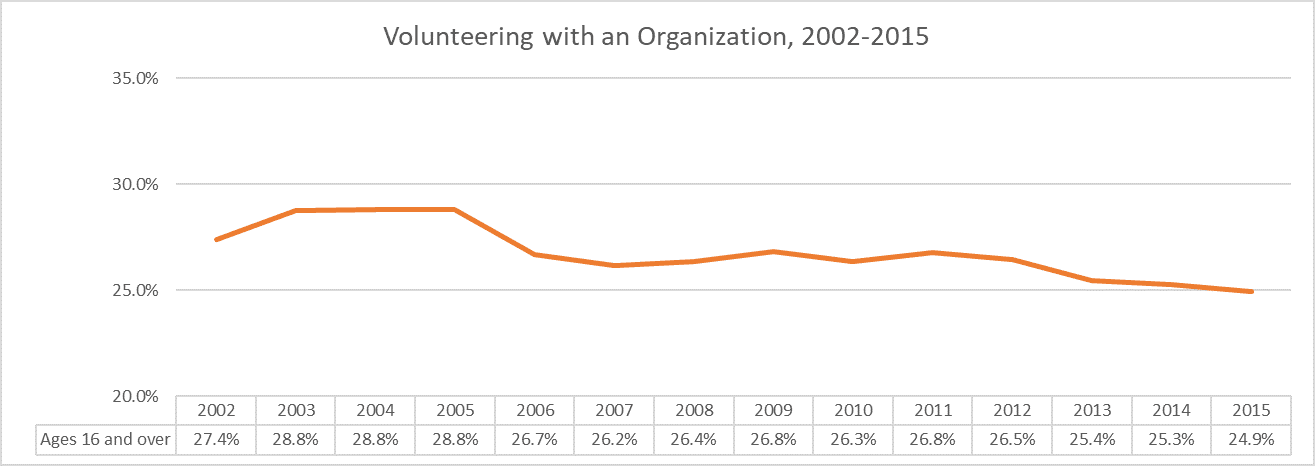

Like recent trends in giving, the volunteer workforce has seen steady declines in the participation rate, but not in its “bottom line” output (hours volunteered). Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. volunteer rate reached its historical peak (28.8%) for three straight years between 2003 and 2005. The national volunteer rate suffered its first large and statistically significant decline in 2006 (falling to 26.7%). The volunteer rate subsequently bottomed out at a 15-year low of 24.9% in 2015. This decline has had a substantial impact on the size of the volunteer workforce: if the volunteer rate had not declined at all between 2004 and 2015, more than 9.8 million more Americans would have volunteered in 2015.

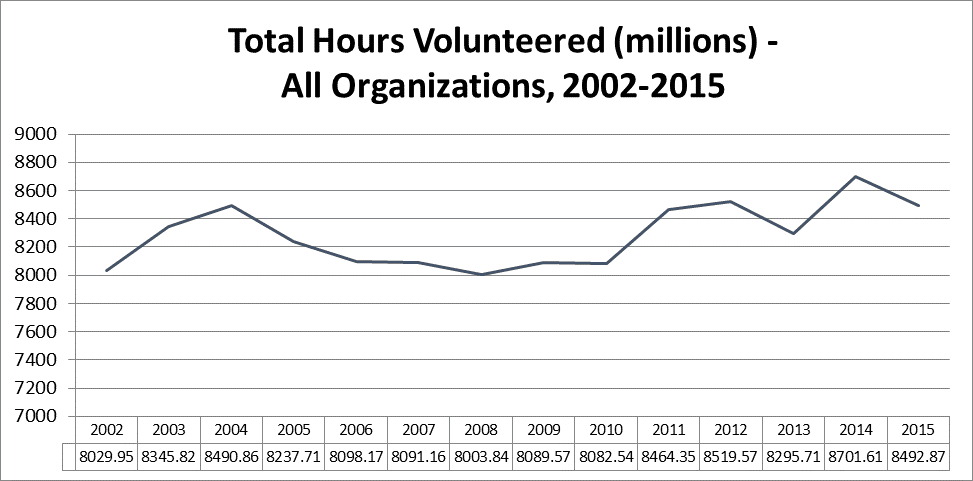

Surprisingly, despite the drop in participation rates, total hours volunteered – the total amount of hours contributed by volunteers (ages 16 and older) to all the community organizations where they serve – has not shown the same decline. Instead, total hours volunteered remained remarkably consistent between 2006 and 2010, fluctuating between 8 and 8.1 billion hours, before reaching a peak of 8.7 billion hours in 2014. This trend tracks charitable giving research that found the total dollars given by donors grew, while the number of donors declined. While these records show those who are volunteering and giving are doing it more, we need to look deeper at why more Americans aren’t giving back.

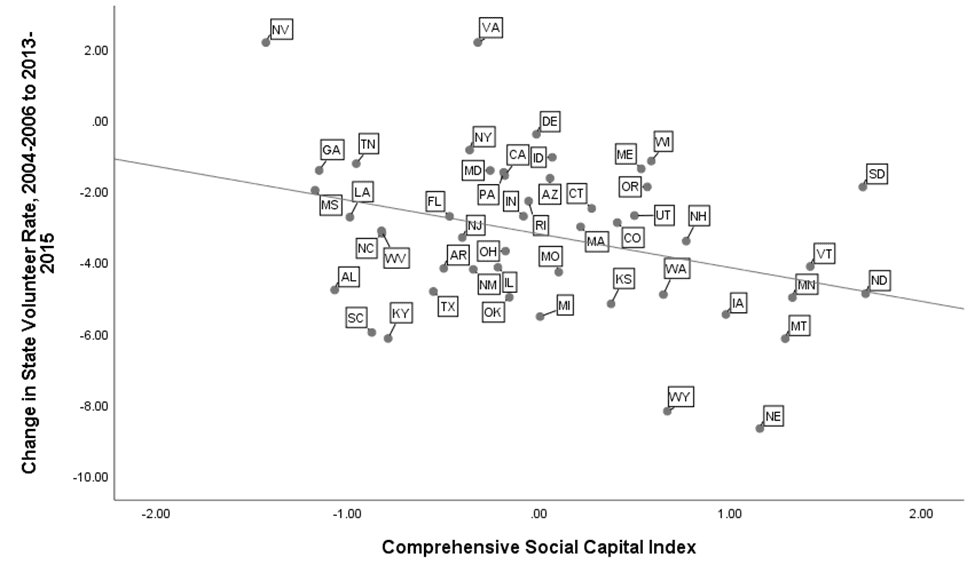

Volunteer Declines Greatest in Historically High Social Capital Areas

Looking more closely, we find that the decline in volunteer rates between the mid-2000s and the mid-2010s was concentrated in certain parts of the country. Between 2004 and 2015, not one state experienced a significant increase in its volunteer rate, while the decline in volunteering is surprisingly more prevalent in states historically rich in social capital, as measured by the Comprehensive Social Capital Index pioneered by Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone. Social capital, which is generated by positive interactions between individuals, is closely related to how, and how often, individuals engage in civic and social affairs. Residents of communities rich in social capital tend to have greater pro-civic attitudes, including trust and reciprocity in others and subsequently a greater desire to be active in community affairs. One would expect areas with high social capital to resist the national decline in volunteering; instead, these states are the most likely to experience declines.

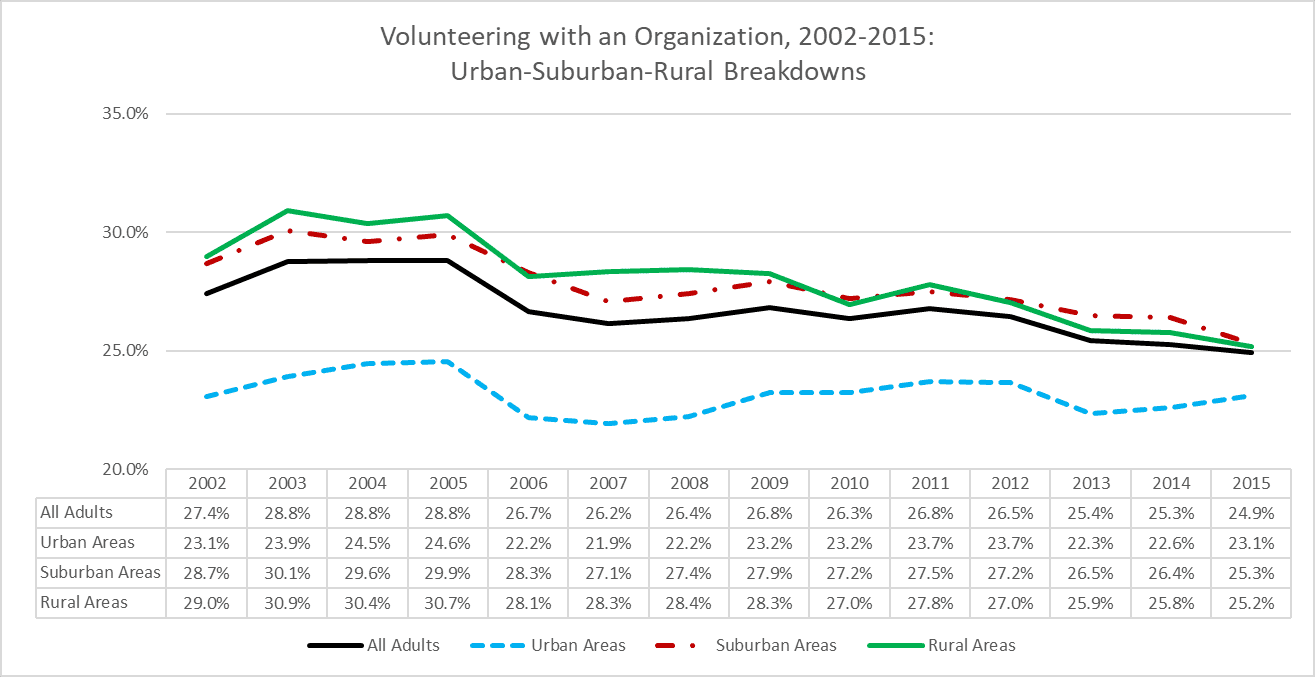

Similarly, rural and suburban areas – which traditionally exhibit much higher rates of social capital versus urban areas – experienced the most significant declines in volunteering. Rural volunteering declined from a high of 30.9% in 2003 to an all-time low of 25.2% in 2015, while suburban volunteering declined from a high of 30.1% in 2003 to an all-time low of 25.3% in 2015. Meanwhile, the 2015 urban volunteer rate of 23.1% was the exact same rate recorded in 2002.

Path to Adulthood Has Changed, Challenging Volunteering

Volunteering is as much about relationships as it is about having the time to volunteer. Historically, volunteer rates reach their highest point for adults ages 35 to 44, and then begin to decline. Declines later in life often stem from retirement, diminished physical capabilities, and the loss of connections with established social networks. The high midlife volunteer rates can be attributed to adults settling into their communities, building and strengthening their social networks and careers, and interacting with more community institutions after having children.

Today, fewer young adults are seeking or reaching milestones traditionally associated with the transition to adulthood, and positively associated with volunteering and giving. These milestones include full-time employment, living independently, owning a home, getting married, and having children. Even today’s young adults who are obtaining or choosing some of these traditional adulthood milestones are often volunteering less than in previous generations. Thus, it is no surprise that young adult volunteering (age 22 to 35) hit a high of 25.6% in 2003 before a long, slow decline to a rate of 21.6% in 2015. With adulthood seemingly getting in the way of community engagement, is there a way to build interest, action, and support for volunteering at an even younger age?

An Urgent Call to Action

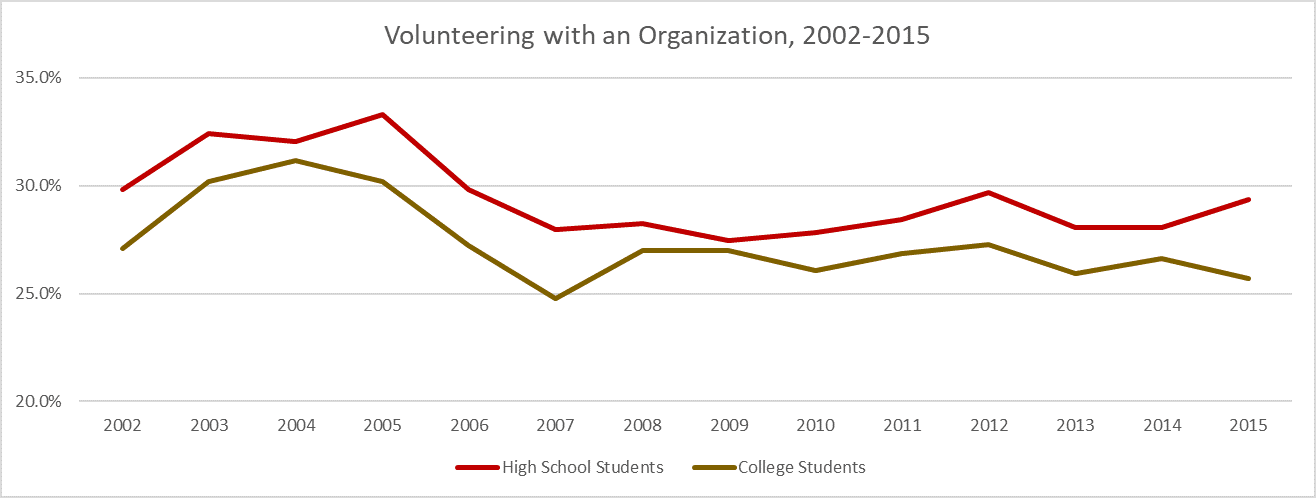

After peaking in the post-September 11 years, the volunteer rates among high school and college students have not declined steadily, but rather have stagnated. Since 2006, the high school volunteering rate has not experienced a statistically significant change, while the college student volunteering rate has not changed significantly since 2008.

Unfortunately, this stagnation has occurred just as record numbers of entering college students express a desire to do good. The annual Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) American Freshman study shows that 77.5% of students entering college in fall 2016 list “helping others who are in difficulty” as an “essential” or “very important” objective, the highest percentage in its 51-year history. The study also shows sharp increases in the percentage of entering college students who list “becoming a community leader” as an important objective. The dichotomy between young people’s intense desire to do good and the overall declines in volunteering, giving, and other informal community behaviors makes finding ways to turn around our growing generosity crisis more urgent.

Volunteers help build a community’s social capital by working together with their neighbors, finding ways to cooperate and compromise, and becoming more aware and understanding of each of our differences. As a nation, we must commit resources and time to the challenging work of putting more Americans back to work improving and engaging with their communities.

Kaitlin Ahmad is the communications manager, Nathan Dietz is the associate research scholar, and Robert T. Grimm, Jr. is the director of the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Independent Sector.

* Between 2002 and 2015, the Current Population Survey (CPS), conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, included a supplemental survey on volunteering, conducted every September. The CPS is also the source of official government statistics on employment and unemployment. Each month, for over fifty years, the CPS has collected data from around one hundred thousand adults in approximately 56,000 households across the United States.