As many people in this country prepare to gather with loved ones and give thanks, some even continuing to pass down the story through generations, we stare squarely at an embarrassing and painful truth: the story of Thanksgiving is a lie, deliberately crafted and told from a specific perspective that has whitewashed the history of and mistreatment of American Indians and Alaska Natives from our national narrative.

Sarah Kastelic (Alutiiq)

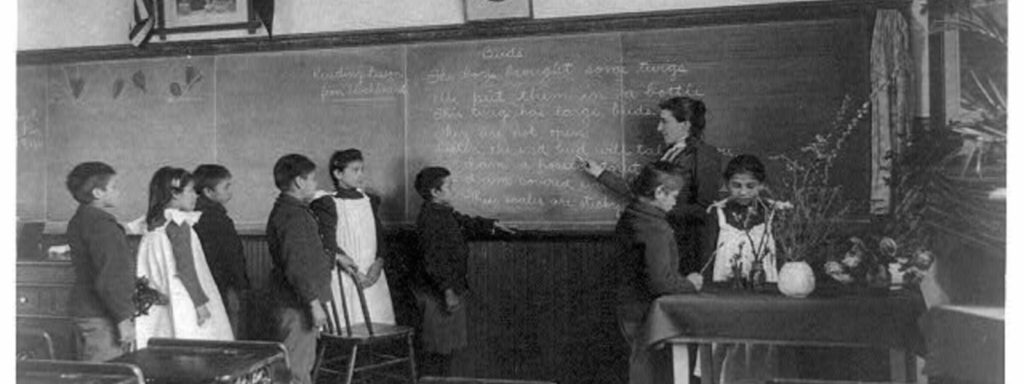

Earlier this year, in May, reports revealed the devastating news about human remains found at residential schools for Native children all over Canada. And beginning about 1869 – more than a century and a half ago – in the United States, but as recently as the 1960s, Native children were forcibly taken from their families and placed in government-funded and/or church-run boarding/residential schools thousands of miles away from their families and communities – all to make them forget their Native culture through forced assimilation into Euro-American culture.

Nothing can make up for the physical, psychological, and spiritual violence and damage that has been done to tribal nations – not renaming Columbus Day National Indigenous Day, not busting the Thanksgiving myth. But a step was taken recently to begin to address the harm done to Native children when U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren and U.S. Representative Sharice Davids introduced the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act.

As we celebrate Native American Heritage Month in November and the rich and diverse cultures, traditions, histories, and important contributions of Native people, we reached out to Dr. Sarah Kastelic (Alutiiq), executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association and Independent Sector Board Vice Chair, about the Act and what it aspires to do.

Illustration courtesy of the National Indian Child Welfare Association

IS: Tell us about the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act. How can it begin to approach even a portion of the historical and intergenerational damage that has been inflicted on Native children and communities?

SK: Companion bills H.R. 5444 and S. 2907 were introduced on September 30, 2021, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, which honors the lost children and survivors of Indian residential schools in Canada, their families, and communities. This Act, with a growing number of bipartisan co-sponsors, would establish a Commission in the U.S. to fully investigate the policy, implementation, and historical and contemporary impact of over 100 years of Indian boarding schools. The legislation facilitates an acknowledgement and truth-telling of the experiences of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian peoples and communities. If passed, the legislation would provide: (1) a full inquiry into the assimilative policies of U.S. Indian boarding schools; (2) a collection of testimony from survivors, tribes, and subject matter experts; (3) the creation and dissemination of Commission findings and recommendations; and (4) a complement to the work of the Department of the Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

This kind of investigation will include a full accounting of the sites where the hundreds of boarding schools existed; the tens of thousands of children who went there; what happened to the children who attended boarding schools, including running away, illness, and death; and the location of graves holding the children’s remains. This is the beginning of a process to understand the long-term impacts on survivors of boarding schools, as well as on the families and communities whose children went to boarding schools and may or may not have returned. Only a full accounting of our painful national history can allow for individual and collective healing.

Photo courtesy of the National Indian Child Welfare Association

IS: The Commission would also collaborate with the Department of the Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in addressing the trauma that has been caused by board schools. What would that collaboration look like?

SK: In June 2021, U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland shared her own family’s experience with Indian boarding schools in an op-ed and later announced the formation of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. She directed the Department to prepare a report detailing available historical records relating to the federal boarding school program in preparation for a future site work. The focus of the investigation is the loss of human life and the lasting consequences of residential Indian boarding schools. The primary goal will be to identify boarding school facilities and sites; the location of known and possible student burial sites located at or near school facilities; and the identities and tribal affiliations of children interred at such locations. This month, DOI is holding consultation with tribal leaders to inform their investigation.

DOI’s work is foundational. It’s necessary but not sufficient. The Commission, with a broader mandate and authority, can collect dispersed information from a much wider set of sources, including churches, the federal government, state and local governments, individuals, and organizations, all of which will build on the DOI initiative.

Art courtesy of the National Indian Child Welfare Association

IS: The Commission would also hold culturally appropriate public hearings, a forum for survivors, victims, families, communities, Native organizations, and tribal leaders to provide testimony on the impacts of Indian boarding schools.

The Commission’s work will culminate in a report with actionable recommendations for legislation and administrative actions to address the impacts of Federal Indian Boarding School Policies.

Could you describe the work of your organization, the National Indian Child Welfare Association, to support American Indian and Alaska Native children and specifically address child abuse and neglect by changing systems at the state, federal, and tribal levels?

SK: For 40 years, NICWA has partnered with tribal governments across the country to prevent child maltreatment. At the federal level, we advocate for policy that acknowledges the rights and responsibilities of tribal governments to care for their citizens. This includes the resources and flexibility necessary to meet the needs of children and families in culturally appropriate ways. We also fight to protect a federal law called the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) that prioritizes keeping Native children connected to their extended family, community, and culture.

At the state level, we work to ensure proper implementation of ICWA, including minimum standards that states have to meet when they work with Native children and families in the child welfare system. We provide training and resources to support best practices in serving Native families, helping jurisdictions to evaluate and strengthen their ability to do so.

At the tribal level, we support tribes in decolonizing their programs. Rather than perpetuating state/county systems that never served Native families well, tribes can turn to their rich cultural heritage of Native child-rearing practices that nurture children and keep them safe. Through our worldview, values, and traditional beliefs, Native cultures have embedded practices to raise happy and healthy children. Drawing on their cultures, tribes can redesign their programs to stop the transmission of trauma through multigenerational child removal and reorient child welfare as a service to help families heal. This necessarily includes not expecting individual parents to solve structural problems like poverty and untreated behavioral health issues by themselves.

IS: How can we begin to change the minds of so many people in this country who find it difficult to let go of the fairy tale they’ve held in their minds throughout generations about the “story” of Thanksgiving?

SK: The Thanksgiving story that most Americans learned in elementary school is a disservice to us all. This sanitized version of genocide is something that we can all choose to re-examine and interrogate. The Smithsonian magazine published a great article about the myths of the Thanksgiving story, based on the book, This Land is Their Land by David J. Silverman, a few years ago.

In educating people about the fiction of Thanksgiving, I particularly like opportunities to dig into Native history and contemporary issues and impact in non-traditional ways. I’d recommend this set of readings and exercises as a way to learn more about Native issues, including representation, repatriation, and recognition.

IS: Sadly, many leaders in civil society organizations and religious institutions directly perpetrated abusive, racist policies, and traumatic practices that have helped kill the culture, spirits, and lives of Native people. What specific steps would you like to see the sector take as a whole to move toward correcting the wrongs that have been inflicted against Indigenous Peoples and throughout the Native communities we serve?

SK: Over the years, many people have asked me when Native peoples and tribes will “get over it” – get over the genocidal and assimilationist policies of our government, complicity of civil society, and ongoing plight and invisibility of Native people. I have two thoughts about this. First, my mentor Terry Cross (Seneca), the founder of NICWA, says, “I’ll get over it when you stop doing it.” The legacy of the past continues today. Our contemporary child welfare system and its disproportionate removal of Native children from their families is simply the modern iteration of Indian boarding schools. It’s not enough to acknowledge the history. We have to stop the systematic and structural ways that policies continue to damage families and perpetuate inter-generational trauma.

Second, Cliff Jones, a trainer and consultant with Capacity Building Partnerships, says, “It’s not my fault, but it’s my responsibility.” What happened in the past is beyond my control, and I didn’t make it happen, but I have the responsibility to do something about it now. As a society, we all do.

Please take the time to learn more about Indian boarding schools in the U.S. Educate yourself about the history and contemporary expressions of these assimilationist policies. As one concrete step, consider how you can be an ally as tribal people and communities work with Congress to pass legislation to create a Truth and Healing Commission. Stand with us as we work to get this legislation passed.

Debra Rainey is communications manager at Independent Sector. Learn more about the Portland, Oregon-based National Indian Child Welfare Association. On November 16, Sarah Kastelic became Vice Chair of the Independent Sector’s Board of Directors. Also, read Kastelic’s first-person essay – “Using My Voice” – which was published by Independent Sector in November 2020. In 2014, she received the American Express NGen Leadership Award. The top photo, which is from 1901, shows an elementary school class of American Indian students at the U.S. Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The photo is by Frances Benjamin Johnston and part of the U.S. Library of Congress collection.