Preserving the Independent Sector

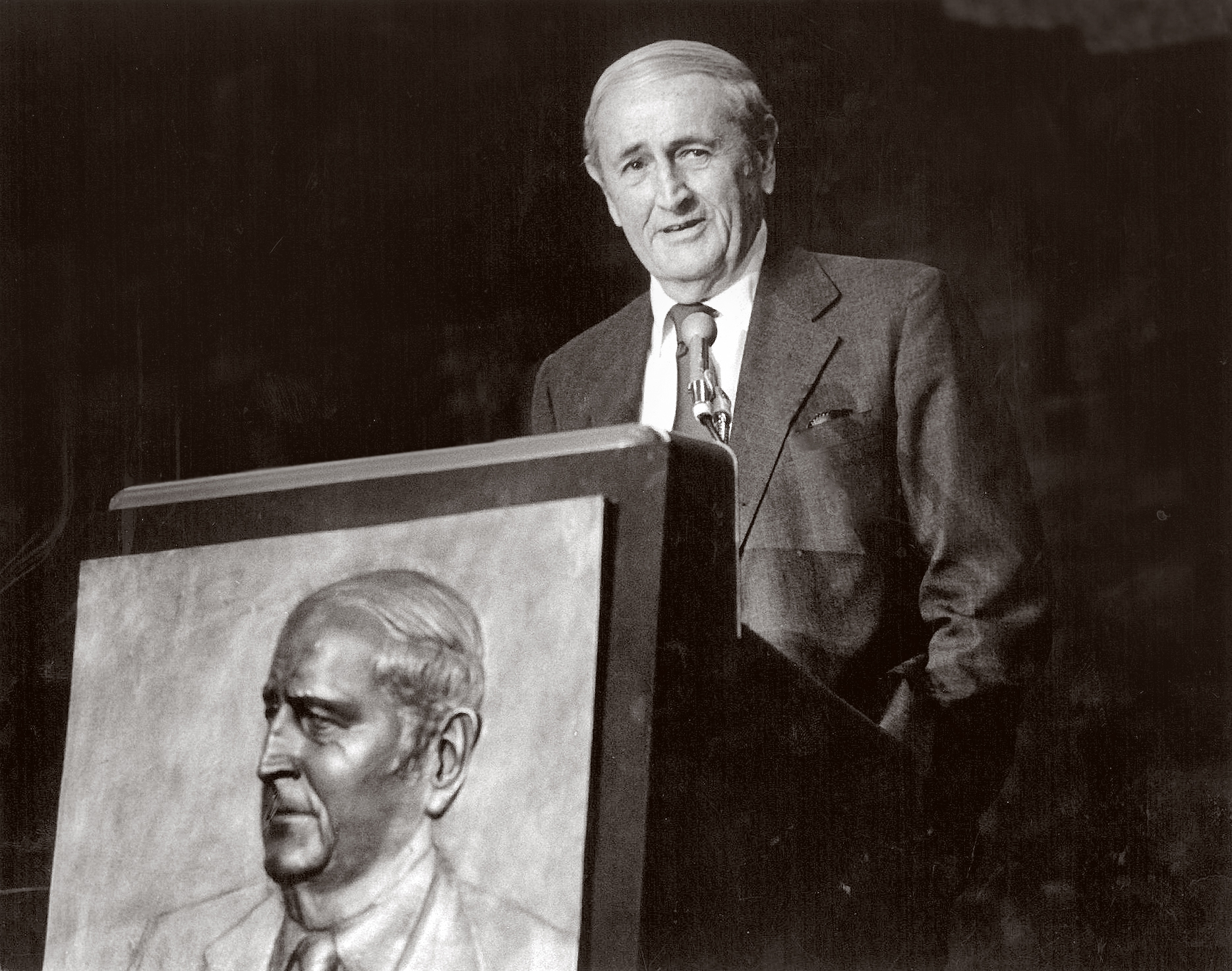

John W. Gardner, co-founder and first board chair of Independent Sector, delivered these remarks in Seattle on May 16, 1979, at the 30th annual conference of the Council on Foundations.

Gardner had an illustrious career: among his accomplishments, he served as Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under President Lyndon Johnson, was president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and founded the advocacy organization Common Cause.

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery

The terms voluntary sector, nonprofit sector, independent sector and third sector are used interchangeably. I shall use the term independent sector for the most part. In this audience, everyone will know what I mean by the term, though no one will know exactly.

In a totalitarian state virtually all activity is, in essence, governmental—and the little that is not is heavily controlled or influenced by government. Almost everything is bureaucratized and is subject to central goal-setting and rulemaking.

In the nations the world thinks of as democracies, there is, in contrast, a large area of activity outside of government. The United States probably outstrips all others in the size and autonomy of its nongovernmental or private sector. The major portion of our private sector consists of activities designed for profit; a smaller portion consists of nonprofit activities. Both profit and nonprofit segments have many dealings with government, but both recognize that their own vitality—whether as profit or nonprofit—depends on the extent to which they can hold themselves free of central bureaucratic definition of goals and prescription of rules.

I am going to talk about the nonprofit segment of the private sector. It is an extraordinary segment of our national life, though Americans are so familiar with it they never look straight at it. It includes religious organizations, organizations concerned with health and welfare, schools and colleges, libraries and museums, performing arts groups, neighborhood organizations, citizen action groups and countless other categories. It includes Alcoholics Anonymous, The Metropolitan Opera, the 4-H clubs, the Amateur Athletic Union, the Urban League, the Women’s Political Caucus and so on and on. The diversity is astonishing.

In recent years, organizations in all parts of this sector have shared an uneasiness. They feel that their place in American life is threatened, that the walls are closing in. They have the sense of a foreshortened future. They worry about the erosion of private giving, about tax policies that may bring further erosion, about the increasingly heavy flow of governmental money into the sector, about the government rulebook that comes with government money.

In 1970, the Commission on Foundations and Private Philanthropy recommended the creation of a continuing body to concern itself with problems the Commission had addressed. Nothing came of it. In 1975, the Filer Commission made a similar recommendation—in somewhat different terms. Again, nothing came of it.

I am heading up the effort to design an organization that might meet some of the needs expressed in those earlier recommendations. My immensely competent partner in that effort is Brian O’Connell, until recently Executive Director of the National Association for Mental Health. Our sponsors are the Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations, familiarly known as CONVO, and the National Council on Philanthropy, each of which has a long list of constituent organizations.

I am chairman of an Organizing Committee, appropriately diverse in its makeup, which plans to complete its work within this calendar year. Obviously, no organization can coordinate the institutions of the independent sector nor speak for the sector—and the last thing we need is another “umbrella organization.”

What we have in mind is a reasonably modest organization that will serve the sector in various crucial ways. Serve rather than coordinate. Serve rather than speak for. We see it as, among other things, a meeting ground for the diverse elements of the independent sector, a place where they can discuss their common problems.

Here are some of the functions that might be performed by this meeting ground organization.

- Working with universities and other research institutions, the new organization will encourage and stimulate research on the sector.

- The organization will undertake the enormous task of public education that must be carried forward if informed Americans are to understand this uncelebrated segment of their national life.

- It will address itself to the problems that arise in the relations of the independent sector to government.

- It will provide a place where the diverse organizations of the sector can share their concerns.

- It will seek to encourage among the institutions of the sector a habit of self-appraisal with respect to standards of performance, accessibility, accountability, uniform accounting procedures and the like.

I’d like to talk further about the new organization, but it’s even more important that we spend some time discussing the independent sector itself.

Most people have a conception of the sector that is limited to the portion they know best. So if you have dealt chiefly, say, with the educational institutions of the sector, I ask you to reflect on the enormous number of religious groups which, statistically speaking, loom over everything else. If you have dealt chiefly with the charitable or social welfare groups in the sector, I ask you to look at the museums, libraries, scientific laboratories and performing arts groups. And whatever your preoccupation, I ask you to look at the diversity represented by the American Arbitration Association, block associations, consumer groups, minority activist groups and the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. Not to mention The Flat Earth Society.

Now that you’re using a wide-angle lens, I want to point out some specially attractive features of the sector. But, before I do so let me offer some words of caution. First, it is not necessary, in seeing the virtues of the independent sector, to denigrate other sectors. Each has its distinctive role to play.

Second, it’s easy to attribute to the sector a role so romanticized and overblown that it’s impossible to live up to. I have read statements on the independent and nonprofit institutions of this country which leave the impression that they are virtually faultless.

We know better. Some nonprofit institutions are so far gone in decay. Some are so badly managed as to make a mockery of every good intention they might have had. There is fraud, mediocrity and silliness. In short, the independent sector has no sovereign remedy against human and institutional failure.

Beyond that, it is the essence of pluralism that it produces some things of which you approve and some things of which you disapprove. If you can’t find a nonprofit institution that you can honestly disrespect, then something has gone wrong with our pluralism.

There should be spirited discussion of the professed purposes and actual performance of nonprofit institutions. Issues such as the accessibility and accountability of these institutions merit searching appraisal.

Now, with those cautious words behind us, let us look at some of the attributes of the independent sector that make it a powerfully positive force in American life.

Freedom from Constraints. Compared with government and business, the independent sector is relatively free. A group interested in a particular idea or program does not have the need of government to deal with huge constituencies, nor the need of the mass merchandiser to find a lowest common denominator. If a handful of people want to start a new religious sect they need seek no larger consensus.

Pluralism. Americans have always believed that—within the law—all kinds of people should be allowed to take the initiative in all kinds of activities. And out of that pluralism has come virtually all of our creativity. Freedom is real only to the extent that there are diverse alternatives. The independent sector offers a rich variety of initiatives, goals, values and beliefs.

An Environment for Innovation. Every institution in the independent sector is innovative; but the sector provides an environment for innovation and creativity. The sector provides a free marketplace whose attributes are in some respect not unlike those of the business marketplace. There is a continuous emergence of new ideas and initiatives. New entities can form overnight—and dissolve just as swiftly. There is freedom to try—and freedom to fail. There is in the sector something of the extravagant redundancy of nature—a thousand ideas can spring up in a single week. If 99,000 of them blow away before the week is over, so be it: the following week another hundred thousand will spring up. The ideas that survive the winnowing will be those that appear to serve some purpose.

In the typical bureaucracy, five new ideas a week would create a painful overload. No bureaucracy could permit a hundred thousand ideas to spring up and if they did spring up it certainly wouldn’t allow most of them to blow away. To do so would imply that some official had failed—either in letting the idea spring up, or in nurturing it after it did.

Virtually every significant social change of the past century—the abolitionists, the populists, the suffragettes, those who sought legislation against child labor, the civil rights movement, the environmentalists, consumer groups—all these and many more sprang up in the nonprofit arena. How long do you suppose we would have had to wait for the contemporary environmental movement to spring up within a government agency? Forever would be a fair estimate.

A Home for Nonmajoritarian Ideas. An idea that is controversial, unpopular or “strange” has little chance in either the commercial or the political marketplace. But in the loose world of the nonprofit sector it may very well find the few followers necessary to nurse it to maturity.

The sector is the natural home of nonmajoritarian impulses, movements and values. It comfortably harbors innovators, maverick movements, groups which feel that they must fight for their place in the sun, and critics of both liberal and conservative persuasion.

Institutions of the independent sector are in a position to serve as the guardian of intellectual and artistic freedom. Both the commercial and political marketplaces are subject to leveling forces that may threaten standards of excellence. In the independent sector, the fiercest champions of excellence may have their say.

Individual Initiative. The freedom from constraints, the pluralism and the constant emergence of new ideas, all provide a strong stimulus to individual initiative and responsibility. The sector preserves in the individual a sense of “the power to act.” As in the for-profit sector, there are innumerable opportunities for the resourceful—to start something, explore, grow, cooperate, lead, make a difference. At a time in history when individuality is threatened by the impersonality of large-scale social organization, the sector’s emphasis on individual initiative is a priceless counterweight.

Opportunities for Participation. To deal with the ailments of our society today, individual initiative isn’t enough: there has to be some way of permitting a natural linkage between individual and community. In the independent sector, such linkages are easily forged. Citizens banding together can tackle a small neighborhood problem or a great national issue. Obviously government provides, through the ballot, the basic constitutional instrument of participation. The enormously varied forms of participation that spring up in the independent sector are not more important—but they greatly increase the possibilities open to the individual.

An Instrument of Community. The past century has seen a more or less steady deterioration of American communities as coherent entities with the moral and binding values that hold people together. Our sense of community has been badly battered, and every social philosopher emphasizes the need to restore it. What is at stake is the individual’s sense of responsibility for something beyond the self. A spirit of concern for one’s fellows is virtually impossible to sustain in a vast, impersonal, featureless society. The independent sector permits the survival of mediating structures that often get squeezed out by modern large-scale organization. Only in coherent human groupings (the neighborhood, the family, the community), can we keep alive our shared values—and preserve the simple human awareness that we need one another.

The countless informal organizations of the independent sector permit the expression of caring and compassion; they make possible a sense of belonging, of being needed, of allegiance and all the other bonding impulses that have characterized humans since the prehistoric days of hunting and food-gathering.

Grassroots Vitality. At a time when the continued vitality of the society requires some measure of decentralization, the independent sector offers an escape from central control and central definition, an escape from clearances with a distant bureaucracy. It makes possible a significant role for relatively small grassroots structures.

The Monitoring of Government. The institutions of the sector are in a position to monitor, evaluate and criticize government. They can set standards. They can propose alternative public policies.

So much for the attributes of the independent sector that I wanted to call particularly to your attention.

Clearly one of the chief problems facing the independent sector is its relationship to government. This is not to suggest that the two are adversaries but to emphasize that the relationship calls for government involvement in the nonprofit sector. Private agencies that receive funds from the United Way already receive, on the average, 25% of their funds from government—and that percentage is increasing. If the trend continues, these agencies will eventually be outposts of government.

Of course, government has been involved in the nonprofit sector since colonial days. But much depends upon the mode of interaction between the two. Some modes of government do not significantly diminish the freedom and flexibility of the independent sector, while other modes stifle and rigidify nonprofit institutions. If we are to balance independence and accountability, we shall have to look at the heavy-handed practices government sometimes uses in dealing with the sector.

Anyone who travels abroad today knows that the steadily increasing role of government is not a uniquely American phenomenon. It is important that we be clear in our attitudes toward the trend as it exists in this country. For my part, I respect our representative government sufficiently so that I want it to function at its best, and to that end I’ve probably had more slugging matches with Congress and the Executive Branch than anyone you know. This nation needs a vigorous government, led at every level by able men and women.

But government must not be allowed to smother the vitality of this extraordinary society. All over this land Americans under no instructions from government—scientists, businessmen, engineers, teachers, artists, nurses, labor leaders, you name it—are solving problems, starting organizations, devising new technologies, helping their neighbors, combatting injustice, pioneering new fields of science, creating jobs, and enriching the lives of others. We love that torrential flow of human initiative, and we intend to hold on to it. Perhaps we’d feel less strongly about it had our history as a nation been different, had we been fenced in early; but now we are too used to the open range.

Within the limits of the law, the independent sector is not subject to central definition of goals, or means to goals. If a half-dozen people organize themselves to revive some long-forgotten philosophy, they do not need bureaucratic clearances; they do not need to prove that it is a high priority social need. They don’t even need to prove that it is sensible. They just do it.

And that is healthy. Several years ago I visited a storefront Pentecostal mission in the most poverty-ridden area of a midwestern city. The director of the mission, himself a product of that impoverished area, believed with all his heart that there was just one priority need: for all to accept the truth of his religious faith. I was accompanied by inner city residents who knew the mission director well and had great affection for him, but their view of priority needs were very different. Most of them believed that the only way to meet the really pressing needs of the people was to provide immediate health care, jobs, nutrition and so on. But one member of the group argued vigorously that an even higher priority is to combat racism, which adds immeasurably to the difficulty of every inner city problem.

The genius of the independent sector is to allow free reign to all of these definitions of priority. To impose a centrally formulated set of goals and definitions would destroy the character of the sector.

In closing, let me recapitulate some of the attributes that make the independent sector a source of deep and positive meaning in our national life. The creativity of the sector is based on its freedom from constraints, its pluralism, its habit of being hospitable to nonmajoritarian ideas, and the opportunities it provides the individual for initiative, participation, a sense of community and grassroots action.

The independent sector is a vital part of our heritage. If it were to disappear from our national life, we would be less distinctively American. It enhances our creativity, enlivens our communities, nurtures individual responsibility, stirs life at the grassroots and reminds us that we were born free. Let us preserve it.