My first job out of college was as a community organizer in Washington, DC. While organizing, mostly Black and Latinx tenants in Columbia Heights, I worked with many people employed in the District’s low-wage economy. People working for private companies, such as hotel, construction, fast food, and retail workers, but also people employed in DC’s vast nonprofit sector, such as museum security guards, childcare workers, social service case managers, college and university food service employees, office receptionists, and charter school teachers.

My 20 years working in the nonprofit sector have taught me that despite our willingness to tackle society’s greatest problems, our industry also struggles to solve many of our own internal challenges. One of those challenges is the inequitable treatment of the people of color that work in our industry. Our society and economy are plagued by an array of racialized economic gaps that manifest in the economic oppression of people of color. These divides include a racial wage gap, a racial wealth gap, and a racial leadership gap that harms the economic well-being of people of color. As an industry, we are lying to ourselves if we think that we are immune from these large-scale racialized economic disparities.

Late in life Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. focused his fight for civil rights on economic justice. In a speech at Stanford University in 1967, he vividly described two Americas, one black and poor and the other white and wealthy. In this speech he said:

“…that the struggle today is much more difficult. It’s more difficult today because we are struggling now for genuine equality. And it’s much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job.”

Key to understanding his intention are the words “genuine equality,” which in today’s parlance we call equity. Even more important, his definition of equality requires the advancement of economic justice. This has resounding implications for nonprofit and philanthropic organizations advancing diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) – the implication being that to truly achieve equity, DEI efforts must advance racial economic justice. More precisely, internal policies and procedures cannot add to the widening of society’s racialized economic gaps, but rather must contribute to their closing.

Following are three racialized gaps that prevent our nation from achieving racial economic justice. By incorporating the closure of these gaps for their employees into our internal DEI efforts, all nonprofit organizations in the industry can join the fight for economic justice.

Racial Wage Gap

Black men and Latinos earn around 70 cents for every dollar earned by a white male. The gap is even wider for Black women and Latinas who earn 65 cents and 58 cents respectively to every dollar earned by white men. This wage gap rolls up into widening racial income disparities, with Black households having an annual median income of about $40k

(about $50k for Latinx households), compared to a median annual income of $68k for white households.

The reason for these disparities are discriminatory policies and practices that undervalue the labor of people of color. We would be foolish to believe that the nonprofit sector is immune from these trends. For example, a study by TSNE MissionWorks that surveyed nonprofits in New England found large racial pay disparities among nonprofit jobs in the region. They found that Black and Latinx employees were over represented in low-paying jobs, and underrepresented in the region’s higher-paying jobs. Addressing these pay gaps could make the nonprofit sector a promising outlier in these problematic national trends.

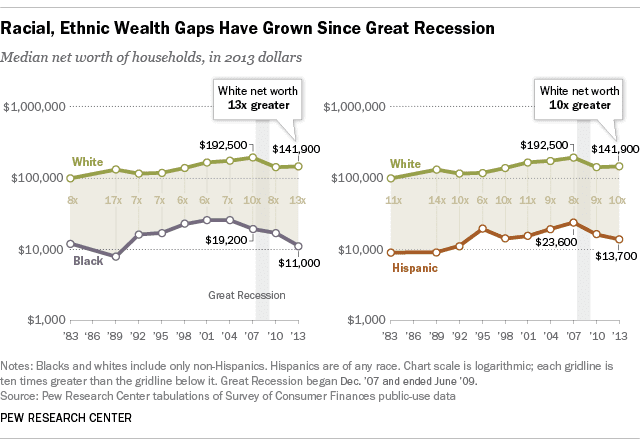

Racial Wealth Gap

The racial wealth gap is another well documented economic divide that has plagued our society for centuries. Wealth is a simple economic equation that combines two countervailing metrics, assets (e.g. home equity, retirement savings, and stock ownership) and debt (e.g. credit cards, home loans, and student loans). Divide a household’s total assets by their total debt and you’ve calculated that household’s wealth. Nationally, White households have 13 times more wealth than Black households and 10 times more wealth than Latinx households. This gap has stubbornly persisted since 1983, when the Federal Reserve began collecting and disaggregating wealth data by race.

The racial wealth gap is the product of centuries of racialized economic policies (e.g. slavery, residential redlining, and discriminatory immigration policy) that have systematically withheld assets from people of color, while simultaneously overexposing them to predatory debt. Examples of things that drive this disparity are retirement savings and student loan debt. Research by the Economic Policy Institute has found that the shift from defined benefit pensions to 401(k) style retirement savings plans has disproportionately harmed Black and LatinX workers. Further, a Brookings Institution study found that Black graduates have been disproportionately harmed by student loan debt (as Black graduates own $7,400 more in debt than white graduates, which triples to a whopping $25,000 after a few years).

In a world where people are retiring later in life, and in a nonprofit industry that relies heavily on people with college degrees, focusing on these two disparities is critically important. For example, since we know that a college degree comes at a much greater cost to a person of color, organizations should take greater care to determine whether a job truly requires a college degree, and if not, remove it as a criterion.

Racial Leadership Gap

Studies have documented that less than 20% of executives in the nonprofit sector are people of color. In 2017, Race to Lead issued a report debunking common myths often used to explain this disparity. By surveying people of color in the nonprofit sector they found that racial leadership disparities cannot be explained by:

- differences in background or qualifications,

- lack of aspiration to lead, or

- deficits in skills or preparation.

Rather, they believe they are more accurately explained by:

- the existence of an uneven playing field,

- the stress of having to represent one’s race, and

- systemic bias baked into the systems of nonprofit organizations.

As leadership roles within the nonprofit sector carry higher pay better benefits, and more stability and security, the closure of this gap has major economic justice implications.

Dr. King called on us to fight for racial economic justice, but we as an industry have not done nearly enough. In fact, when it comes to our own employees, many nonprofits have adopted the very same employment policies and practices responsible for the racial wage, wealth, and leadership gaps that plague our society and economy. As an industry, we must come to terms with the truth – if we are not part of the solution, then we are the problem.

Jeremie Greer is the co-founder and co-executive director of Liberation in a Generation, a new racial and economic justice organization that seeks to galvanize the political power of people of color towards their own economic liberation. He is also an Independent Sector Policy Fellow.