Photo: Jonathan Rose Companies / rosecompanies.com

Imagine a beachfront condo where a buyer can specify “posture-supportive heat reflexology floors, mood-enhancing aromatherapy, and vitamin C-infused showers.” Just outside your front door at Amrit are “lifestyle programs carefully curated to address sleep deprivation, nutrition and diet, relaxation and de-stress, personal training, fitness and sports rehabilitation, beauty treatments, [and] weight management, just to name a few.”

If you’re looking for a healthy lifestyle but the beach isn’t your thing, consider Serenbe, a 40,000-acre preserve near Atlanta where “wellness is an everyday activity” fostered by “a network of well-worn footpaths,” making it easy to walk to yoga class or the weekly farmer’s market.

With a certified organic farm, three farm-to-table restaurants, and a community-supported agriculture program, “Serenbe feeds our residents in more ways than one … We need fresh air, fresh food, trees and grass around us. We need a place to grow and restore – a place to foster deep connections and connect with living systems.”

Amrit and Serenbe may sound utopian, but they are hardly unique. Developers across America are pouring more than $50 billion into “wellness communities” where the built environment encourages exercise, fresh air, and stress reduction.

Does it work? According to the World Health Organization, up to 90 percent of individual health outcomes are linked to environmental factors like air quality and access to fresh foods. By building with a healthful environment in mind, developers say they can literally change lives.

“There’s a health benefit coming out of almost every household,” Serenbe founder Steve Nygren recently told Fast Company, “whether it’s the kids don’t have asthma and have less allergies, or people have gotten rid of their antidepressants.”

* * *

“The kids don’t have asthma” is a phrase you’ll never hear in the South Bronx, about 900 miles from the footpaths and farmer’s markets of Serenbe. This is a neighborhood with some of the highest asthma rates in the country, and asthma-related hospitalizations are five times the national average.

At 37 percent, food insecurity in the South Bronx is higher than anywhere else in the country (and more than twice as high as the rest of New York City). Even those who manage to eat enough often don’t eat well: The neighborhood is known as a food desert, where it’s easy to find burgers or sodas but hard to find bananas or spinach. It’s not surprising, then, that obesity rates for adults in the South Bronx (age 45 to 64) are 50 percent higher than New York City as a whole.

If you wanted to test the hypothesis that a wellness community could help mitigate health risks like obesity and asthma, then surely the South Bronx would serve as the perfect laboratory. But of course there’s one major problem: wellness communities are expensive, and the market here simply can’t support vitamin C showers or meditation gardens. Poverty rates across the South Bronx exceed 40 percent, the rate of home ownership is less than 7 percent, and up to half of all housing units are public or rent-subsidized.

The bottom line is this: If you’re a low-income person of color in the South Bronx, you have almost zero chance of living in a home designed to promote better health.

Why “almost”? Because of a 1.5-acre sliver of land – formerly a rail yard with contaminated soil – where a for-profit developer and a nonprofit housing organization teamed up to prove that green and healthy aren’t only for the great and wealthy. The project, known as Via Verde, opened in 2011, well before the current craze for wellness communities. Seven years later it’s still a shining example of how a community-based nonprofit can promote equity, no matter what its specific mission area may be.

* * *

Photo: Jonathan Rose Companies / rosecompanies.com

Founded in 1905, Phipps Houses has grown to become New York City’s largest nonprofit developer and manager of affordable housing. In addition to housing, the organization offers social services like after-school programs and summer jobs through its affiliate, Phipps Neighborhoods.

In 2006, when New York City unveiled a competition to promote affordable housing that was innovative, green, and healthful, Phipps teamed with Jonathan Rose Companies, a national developer with $1.5 billion in real estate under management. Their vision was audacious, bordering on utopian: Via Verde was designed to maximize light and airflow, rather than maximizing price per square foot. Stairways would be conveniently placed and punctuated by windows, encouraging residents to forsake elevators. A neighborhood medical clinic would occupy the first floor, and a fitness center would crown the building, overlooking a 40,000-square-foot green roof where residents could grow fruits and vegetables or simply go for a stroll.

When the vision became reality in 2011, would-be residents flocked to the project, hoping to find a home that would recognize their aspiration for a better, healthier life. Demand outstripped supply by more than 10-to-1. Even the architecture critic for The New York Times was impressed with what Via Verde had achieved:

“Unlike so many public-housing projects,” Michael Kimmelman wrote, “Via Verde rethinks the mix of private and public spaces to encourage residents to spend time outside, in the fresh air. It breaks the mold of subsidized housing whereby clinics, low-income rentals and home ownership are all conceived, financed and regulated separately. Piecing them together, it takes the healthier, holistic tack. Healthy design comes down to fundamentals in this case: air, light, places to stroll, things to look at.”

* * *

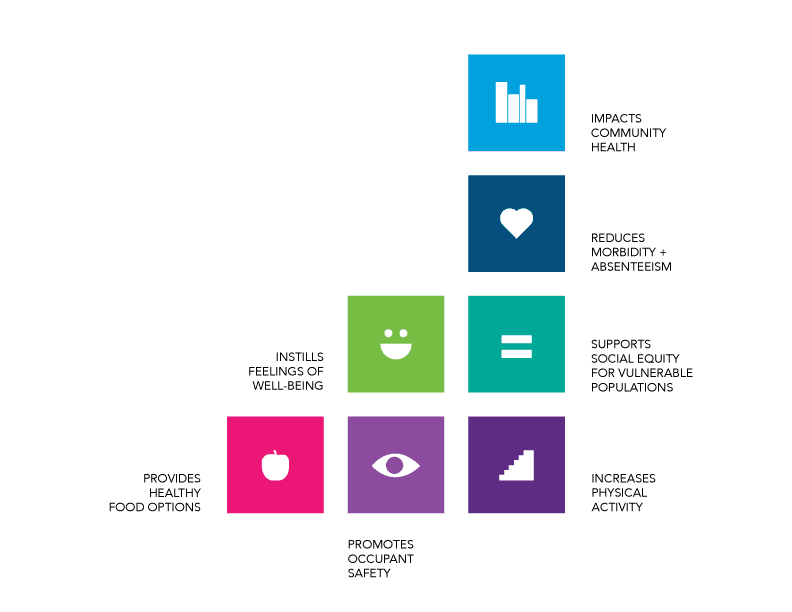

Fitwel Health Impact Categories. Courtesy of the Center for Active Design. Learn more at: https://fitwel.org/standard

If just a handful of design “fundamentals” can truly yield health benefits for all, then why can’t every community be a wellness community, regardless of price point or demographics?

That’s a question that Joanna Frank asks herself constantly. As president and CEO of the nonprofit Center for Active Design (CfAD), Joanna believes that “standout projects” like Via Verde are no longer enough. With more than a decade of research establishing the economic and lifestyle benefits of healthier housing, “at this point, it should be a matter of scale and moving to standard practice. Our mission is to achieve market transformation of design and development practice to support health.”

One method for achieving scale is Fitwel, a new certification program that scores affordable housing developments against more than 55 evidence-based standards for healthier design.

Attractive, well-lit stairwells, infrastructure for walking and biking, community gardens and safe playgrounds: When CfAD certifies a project under the Fitwel standards, developers gain access to special financing from Fannie Mae that can save millions of dollars on the typical 30-year mortgage.

Joanna believes that Fitwel solves the ROI problem for developers of affordable housing, so she’s not surprised that initial interest has been strong. Just a few months into the program, several projects are undergoing the certification process and one – an $18 million renovation of Atlanta’s Edgewood Court – is currently underway.

The goal of all this, according to Joanna, is “a more equitable built environment” for people of every income level. “We know that residents of affordable housing are suffering from disparities in education, wages, and other outcomes. We can’t solve everything but designing for better health is something we can do. It’s all based on research and evidence. We have metrics. We can speak to impact. It’s important that this movement becomes ubiquitous.”